APHRODITE'S NOSTALGIA

Click here to order your copy

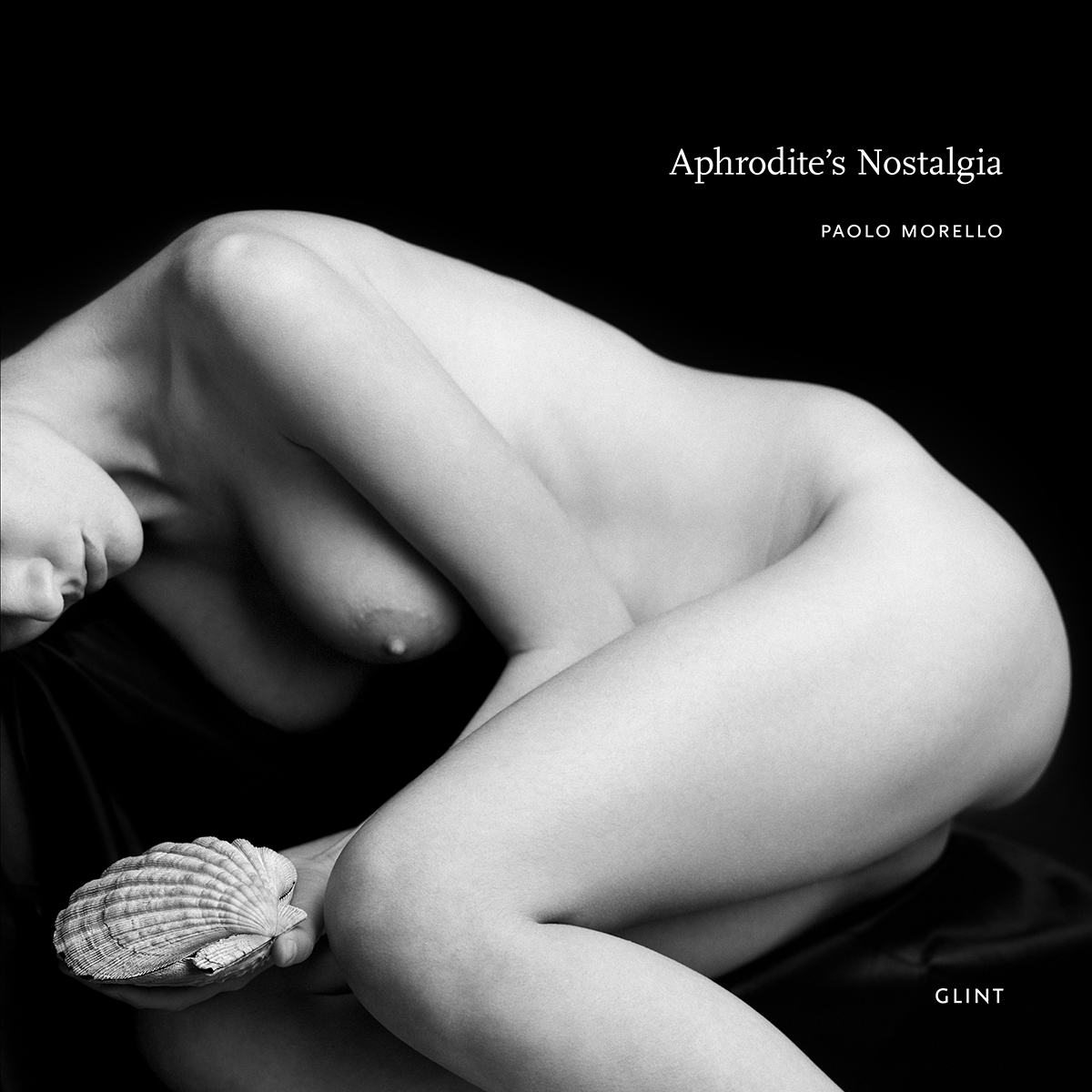

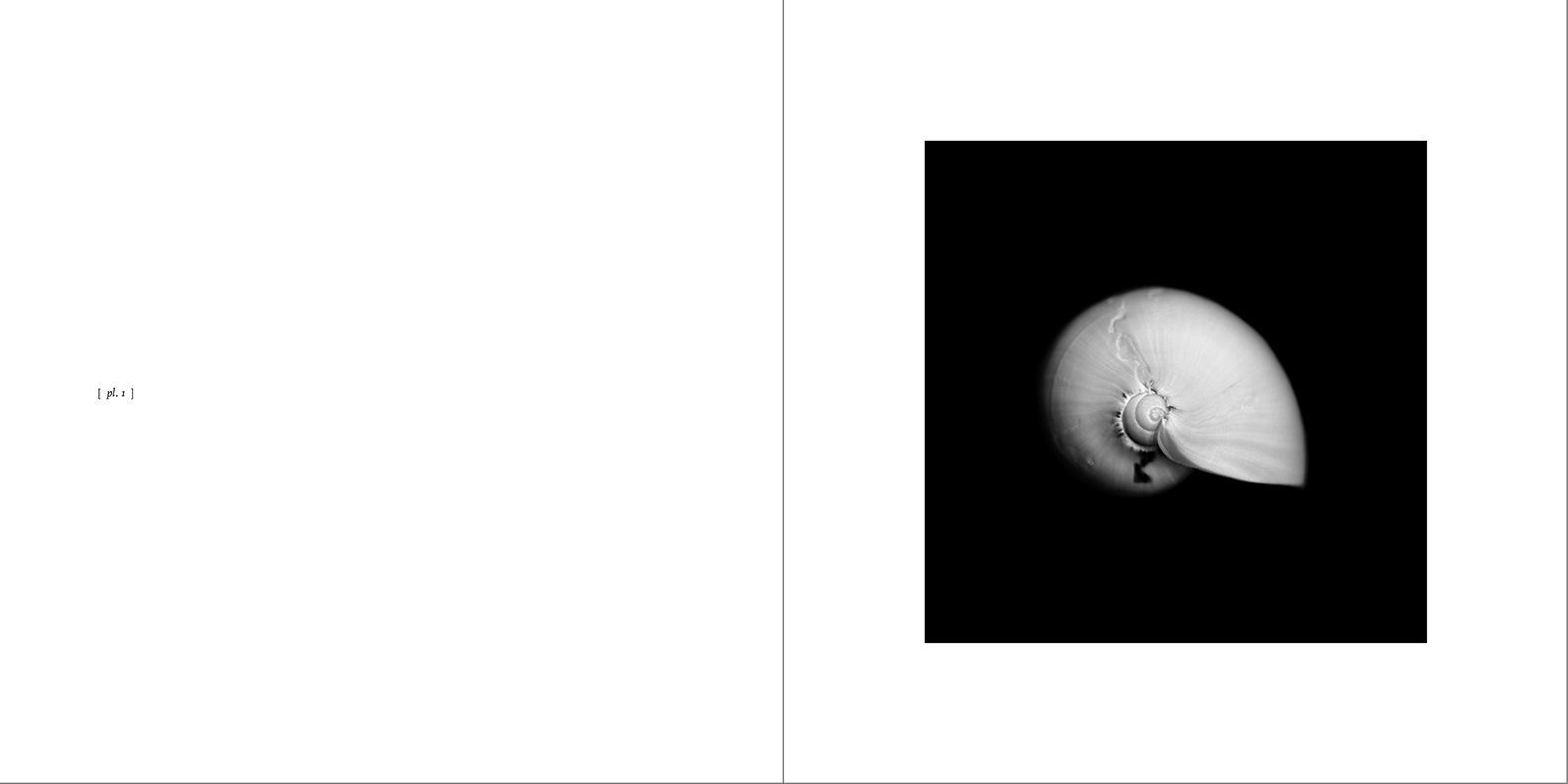

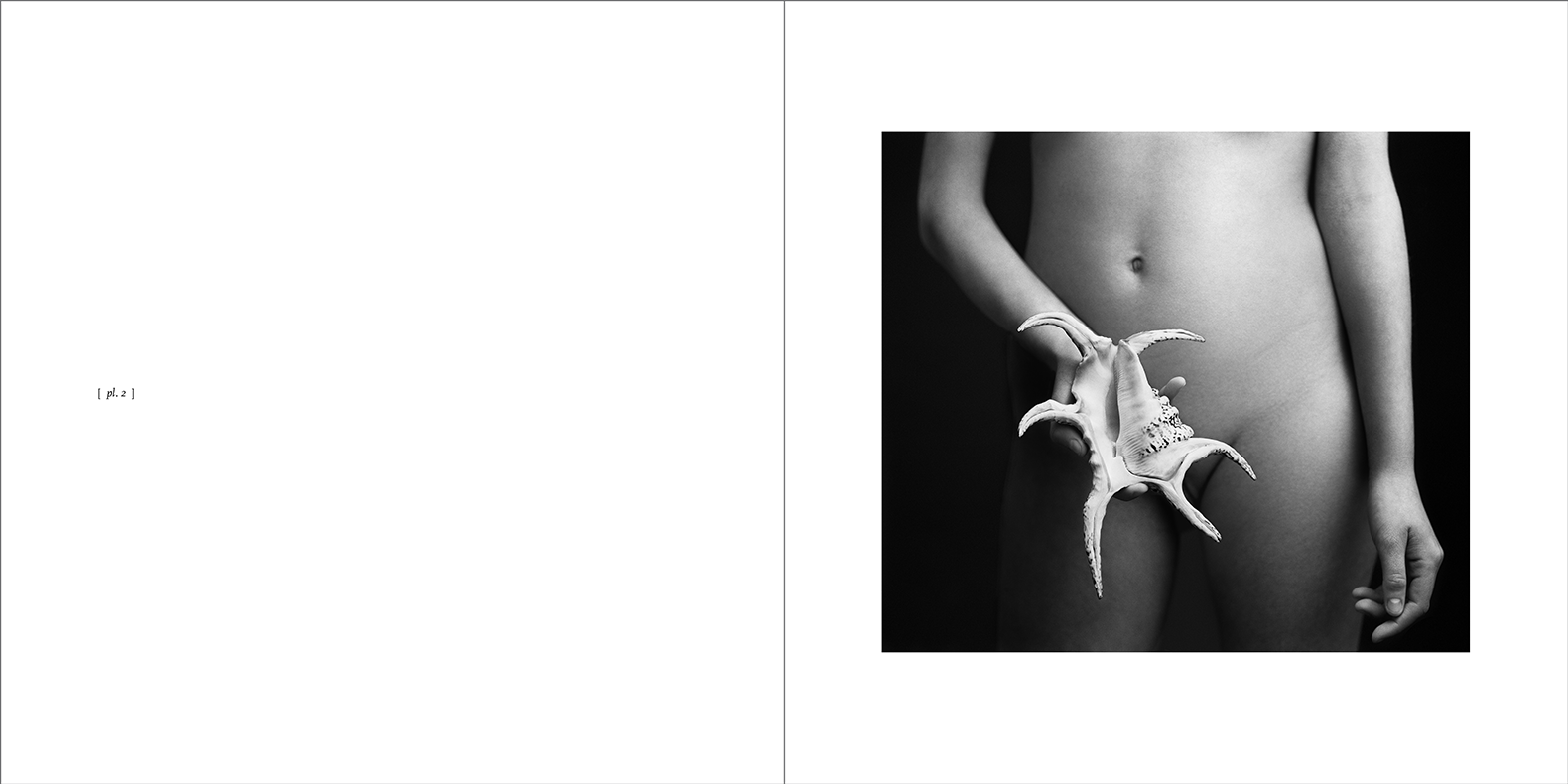

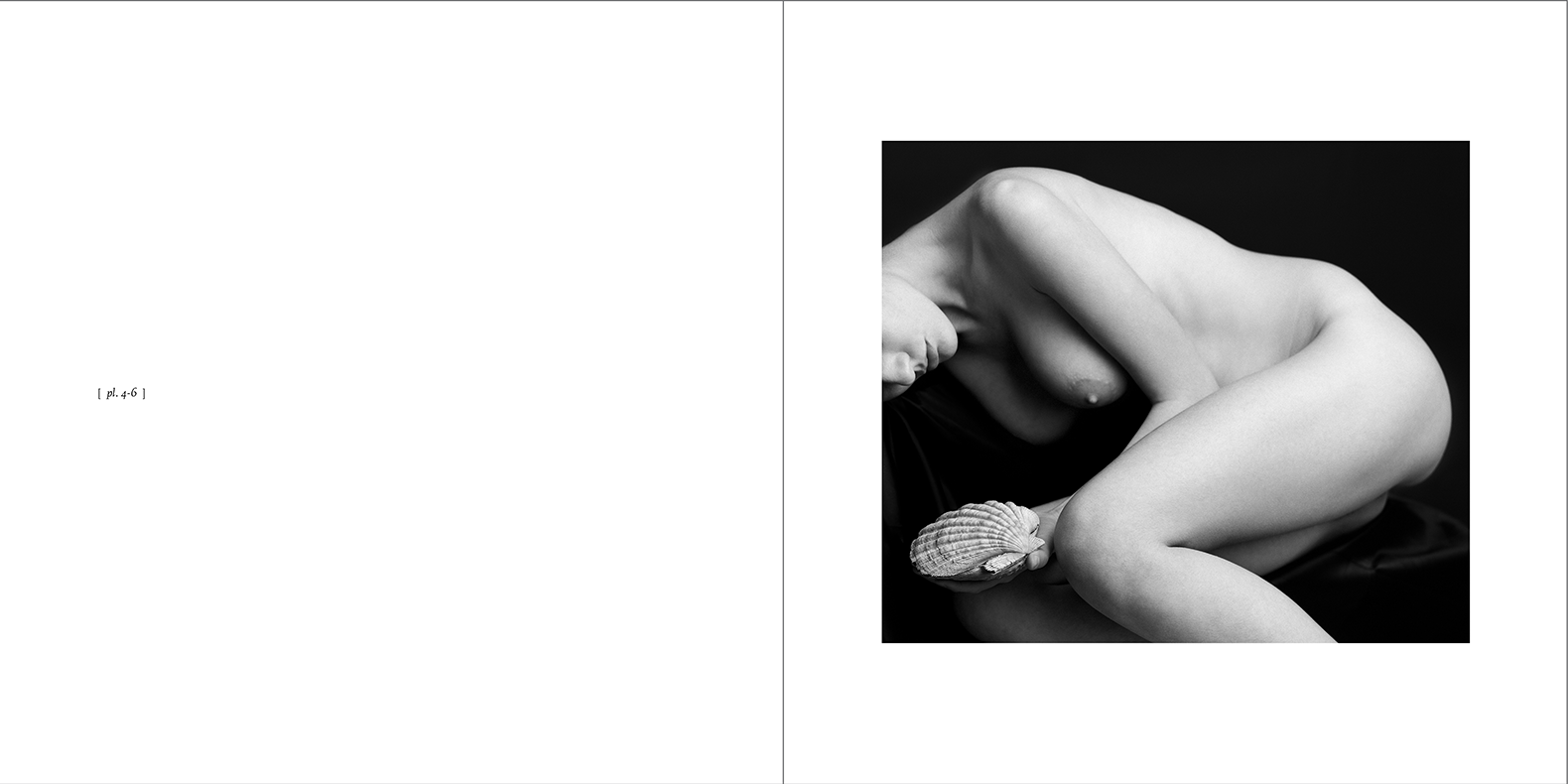

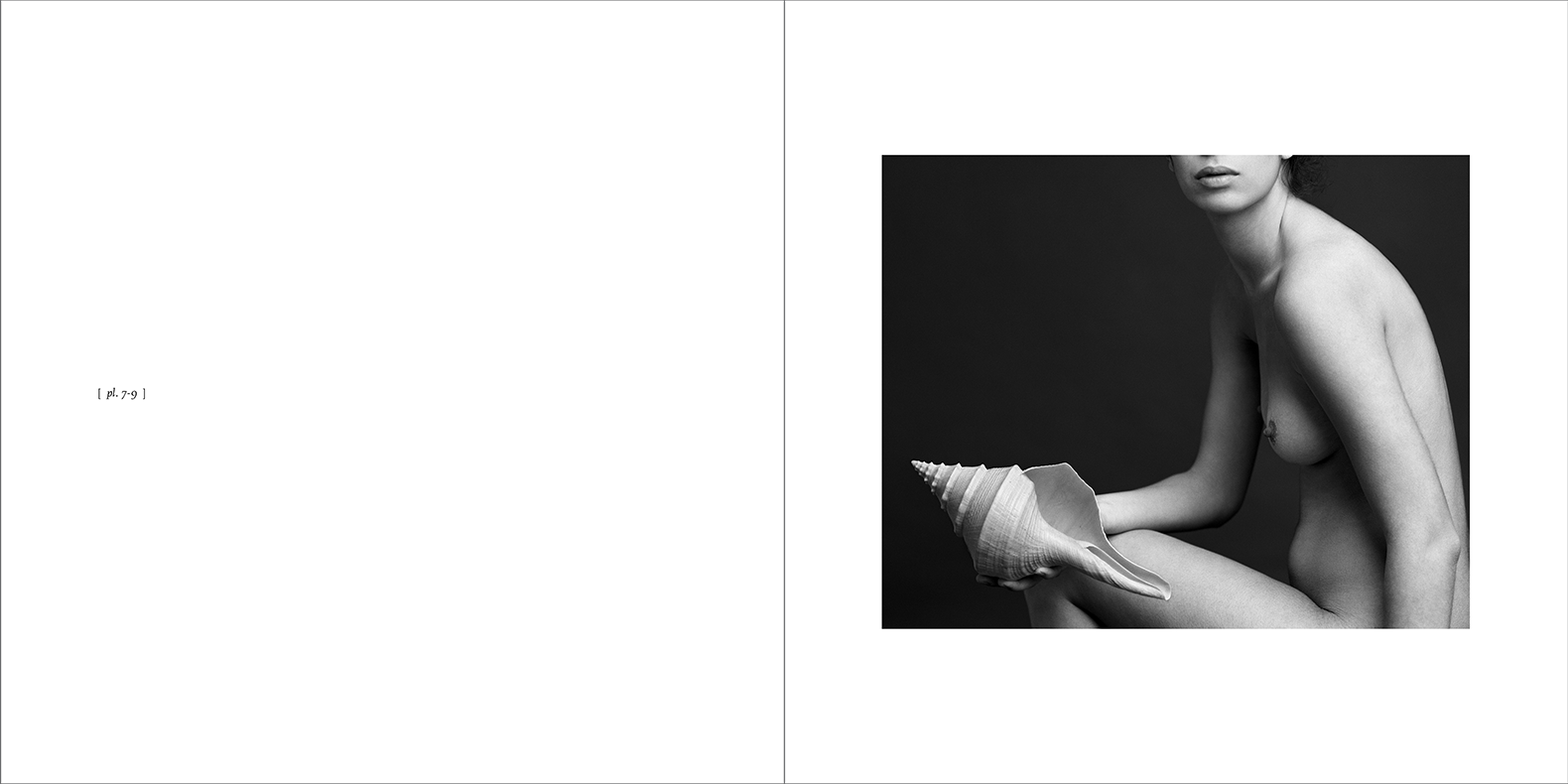

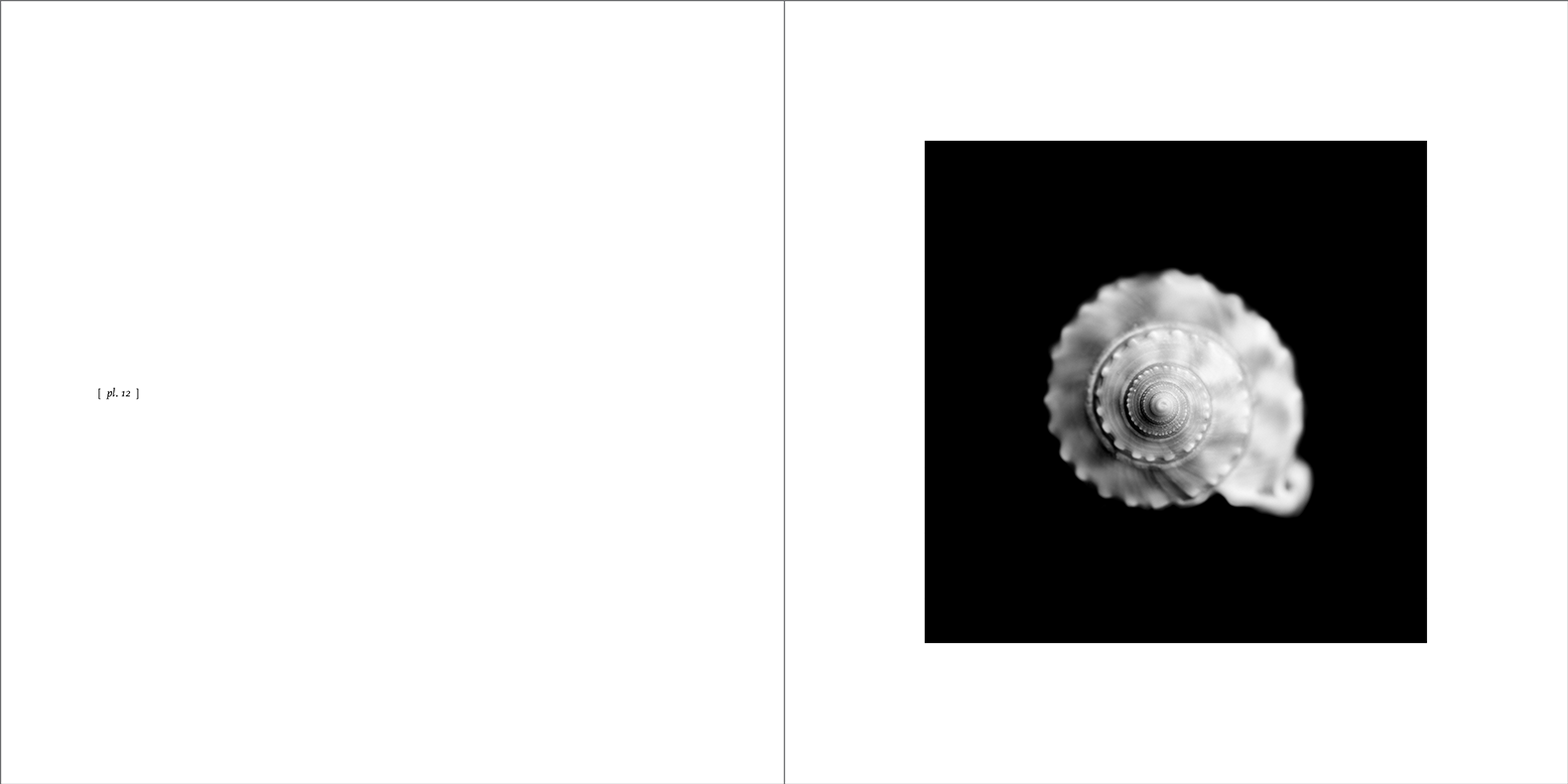

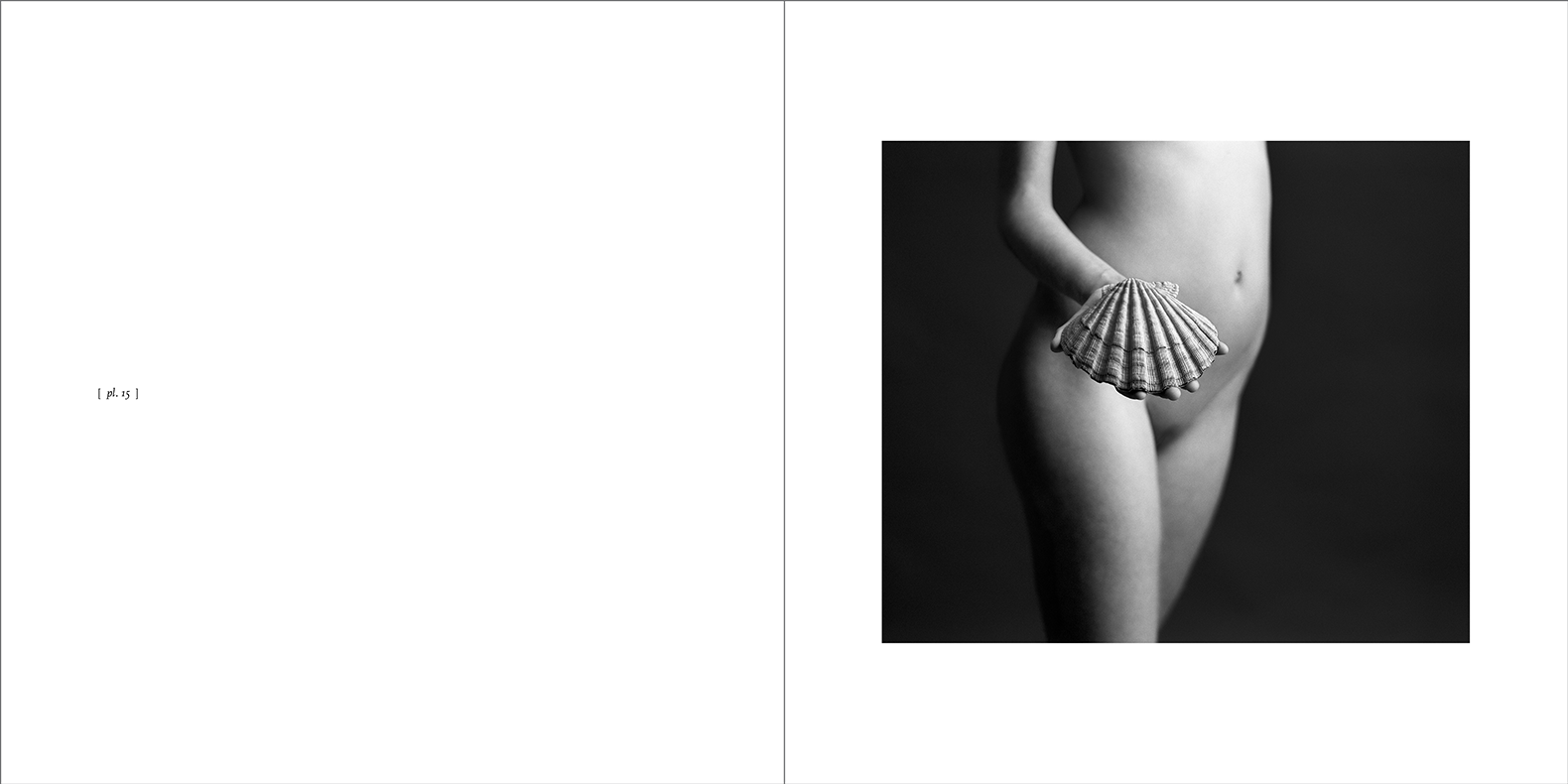

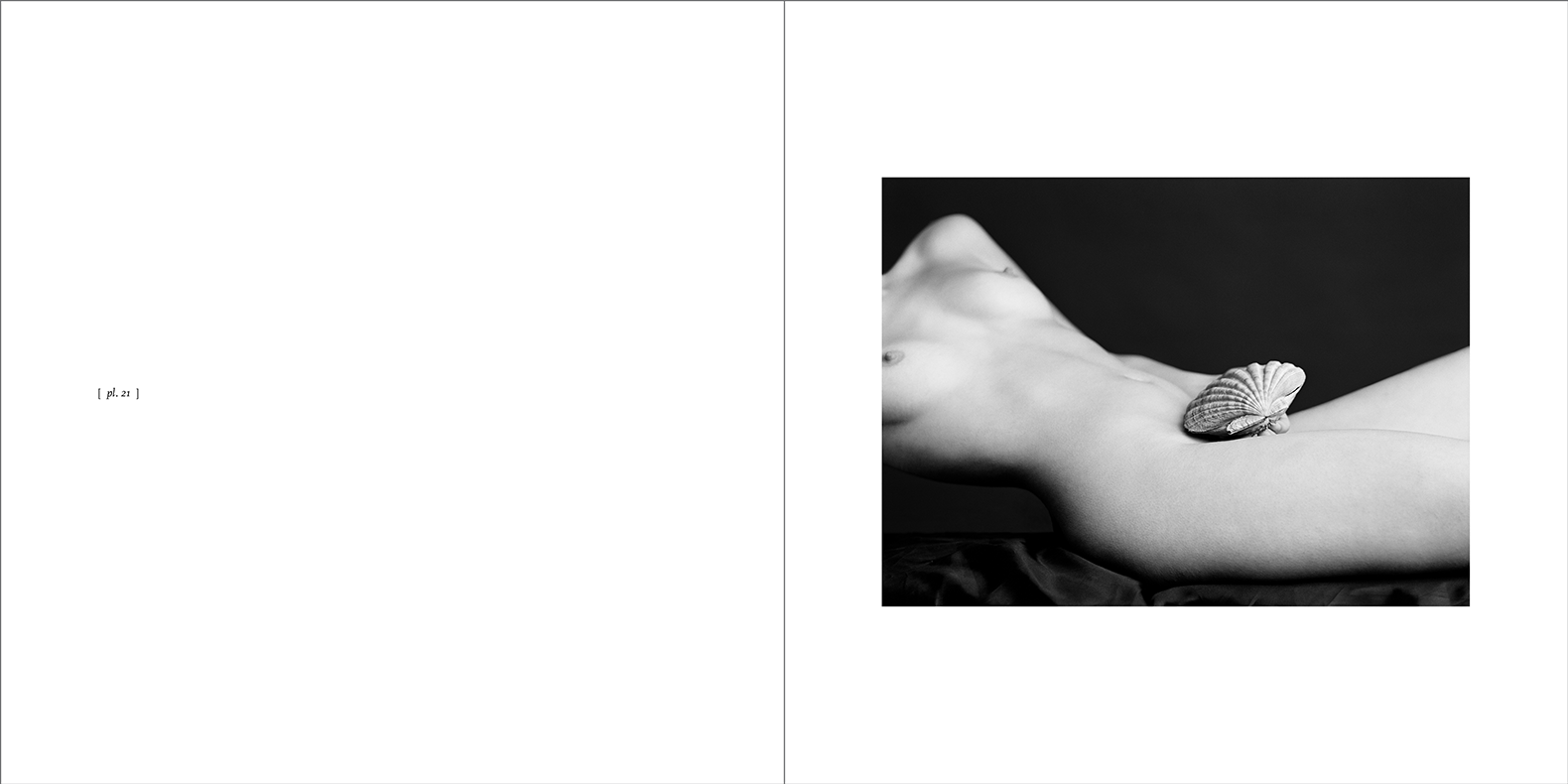

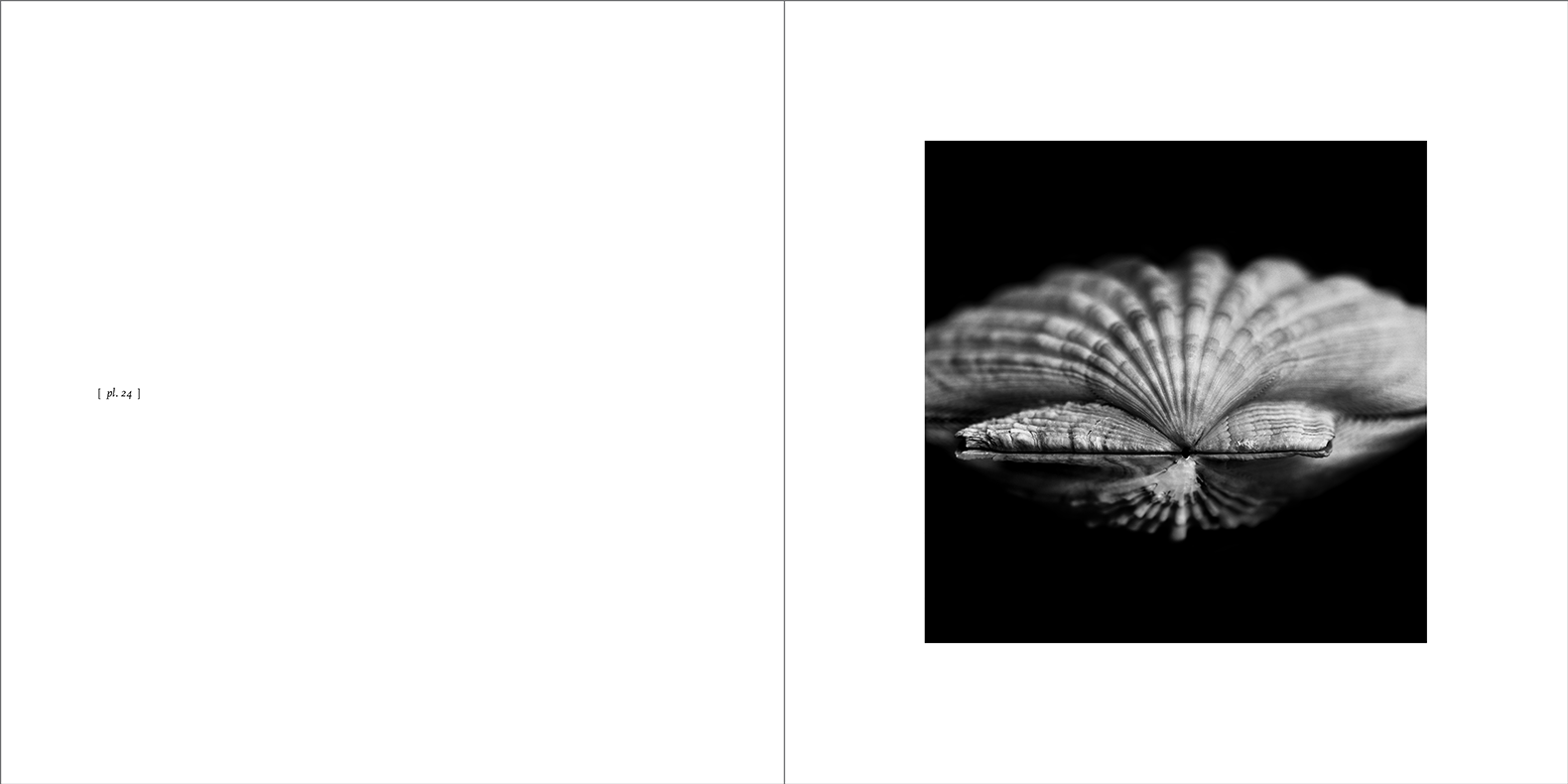

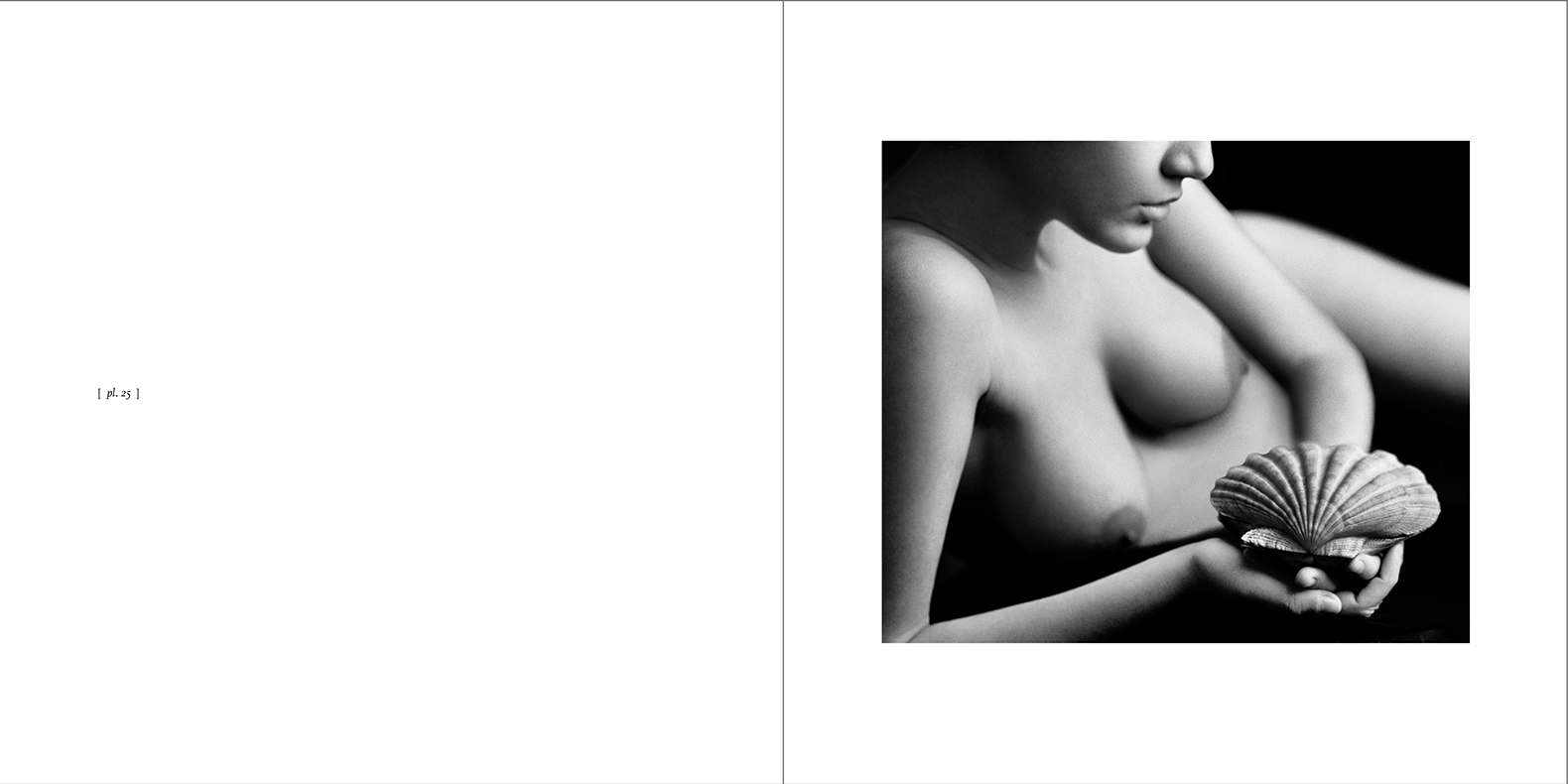

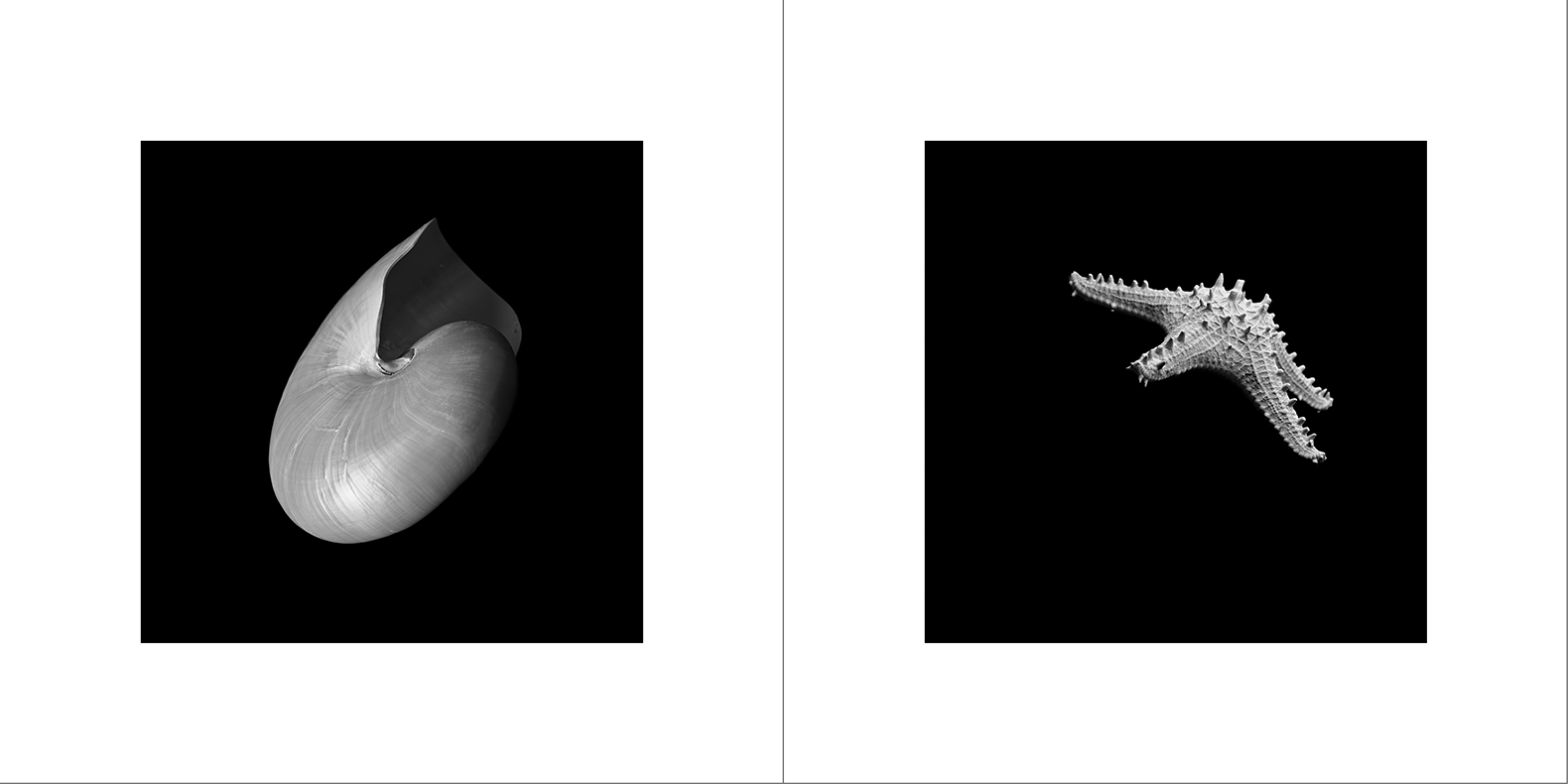

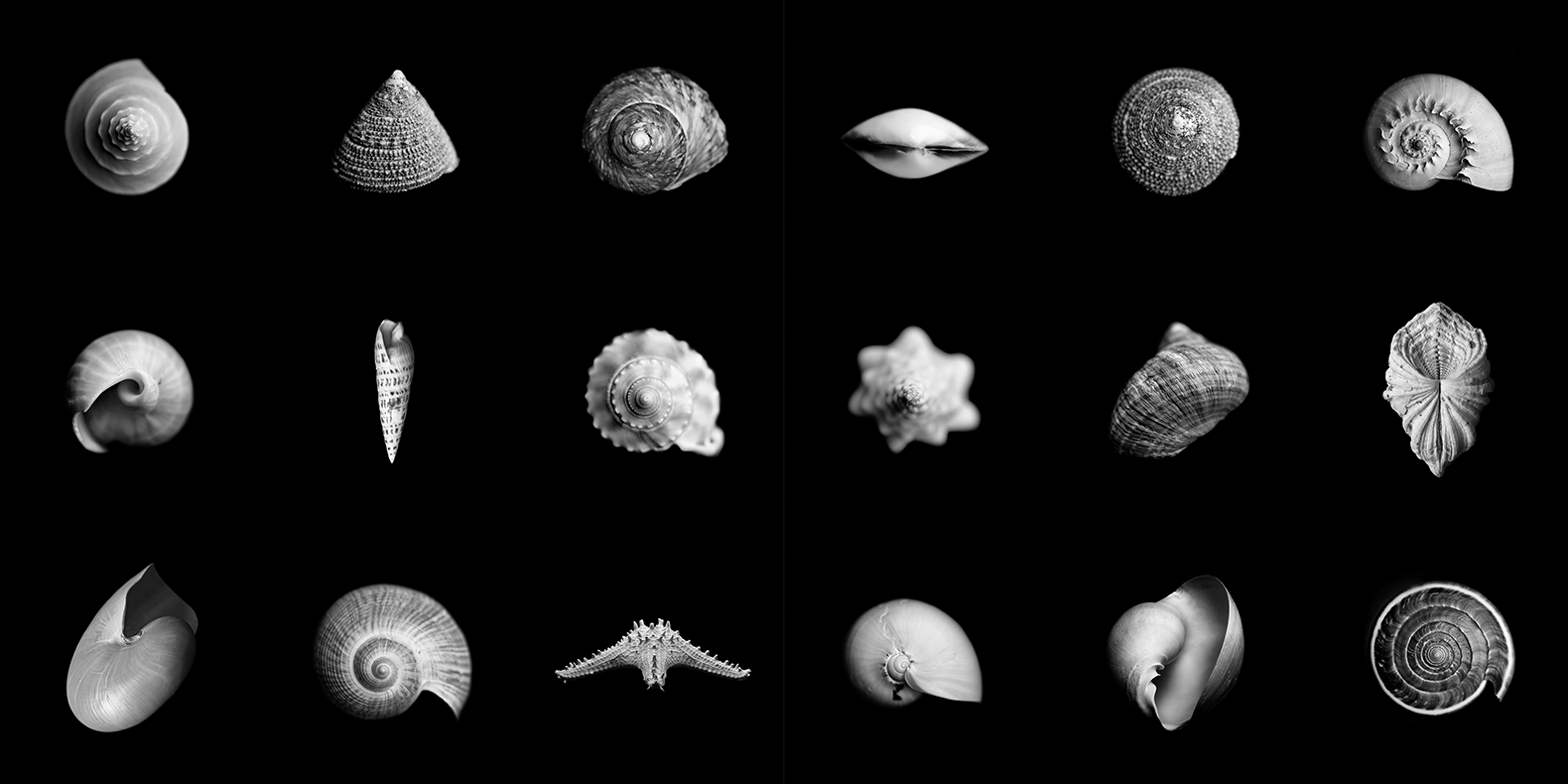

Myths, as Károly Kerényi wrote in his Essays on a Science of Mythology, never explain causes (aithia), but rather principles, or more precisely, origins (archai). The ancient Greeks were familiar with the idea of Origin. They had an intimacy with this word which we have totally lost. Dozens of myths tell about Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty and love, of sensuality and voluptuousness, and dozens of early works of art represent her associated with the shell, the symbol that perfectly mirrors her. Yet a closer study reveals a more structured and controversial relationship between the goddess and the shell, and – what is more interesting – one that is open to new meanings. Before being the goddess of beauty, love, and sexuality, Aphrodite was the goddess of Origin. Her role was to embody the mystery of Origin, the same mystery that is concealed by the fleshy lips, the perfect spirals of the shell.

Long regarded as symbols of femininity, both the goddess and the shell represent an archetypal image of Origin. May not these two terms – femininity and Origin – be closely connected to one another? May not giving origin to be the first, fundamental role of every woman? May not this first experience – being generated by a uterus – be common to every mammal? What memory, or unconscious trace, do we retain of this experience? Do we continue to nurture the memory of our Origin, or have we forgotten it? What then if one day Aphrodite were to feel nostalgia for her own origins? What if one part of our unconscious were to act under the pressure of this feeling?

The once profound link between Aphrodite and the shell has worn out. Now the goddess looks at the shell as a foreign object that no longer belongs to her. It is precisely this sentiment – the awareness of not belonging to one’s own symbol any more – that these photographs attempt to represent. A feeling of amazement and at the same time one of nostalgia.